By Justin Sanders

Even for the most well-adjusted among us, high school is a time when it’s easy to slip into loneliness, depression, and even despair. For Samantha Ramirez-Herrera, whose family moved to Arizona from Mexico when she was six years old, such feelings were a foregone conclusion.

“High school was when I started realizing the impact of being undocumented,” she told CreativeFuture. “Everybody was getting ready to take the SATs and apply for college… but these were things we didn’t even discuss in my home. We didn’t talk about college or furthering our career – because we were undocumented. We couldn’t tell people about our status because something bad could happen, so it was this secret that I was just holding. I didn’t tell any of my friends. I didn’t have anyone to talk to about it.”

Before the DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) immigration policy was in effect, before the term “Dreamers” was part of the national vernacular, there was little to no recourse for young people like Ramirez-Herrera. At 17, she believed she would be stuck in Arizona, “working at a low-end job forever, because I don’t have a social security number to get a real job, or to go to college,” she said. “Even if I had good grades, I couldn’t have gotten a scholarship. I couldn’t apply for financial aid.”

Now 33, Ramirez-Herrera is a filmmaker, creative director, writer, mother, feminist, civil rights activist, and DACA recipient living in Atlanta. She is the founder of OffThaRecord (OTR), a creative content agency and digital magazine whose clients include the likes of Johns Hopkins Medicine, Macy’s, Stacey Abrams, and the Ms. Foundation cofounded by Gloria Steinem. The story of how she got here, against all odds, is remarkable, and it’s a story she tells remarkably well – thanks to frequent speaking engagements and appearances in outlets ranging from Forbes to Hardball with Chris Matthews. It’s definitely the most inspiring thing you will read today, and I count my lucky stars that she was willing to tell it to me.

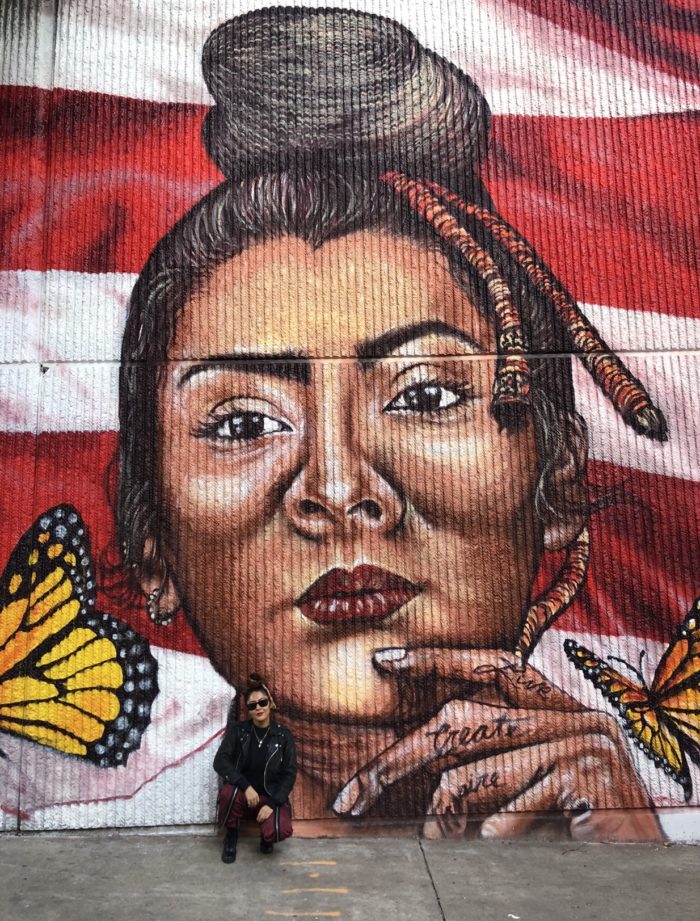

The day we spoke was close to Super Bowl Sunday, and a giant mural featuring Ramirez-Herrera, along with three more of her fellow dreamers, had just been unveiled on a downtown Atlanta building in honor of the occasion. Our conversation began there.

JUSTIN SANDERS: Hi Sam! What’s happening?

SAMANTHA RAMIREZ-HERRERA: [Laughs] Well, I literally just walked out of my office and saw a giant mural with my face on it! The Super Bowl is in Atlanta this year, and they had a contest for painters around the city to paint murals for the game with a social justice theme. A Latina painter named Yehimi Cambron won the contest and she decided to do a mural featuring four different influential Dreamers. So, she included me in the mural, and now they’re projecting it on a huge building down by my office!

JS: What an amazing statement about the power of undocumented immigrants – even in these turbulent times. Your own family emigrated from Mexico when you were a young child. What comes to mind when you think about those early days in America?

SRH: My family came to America when I was six, two months before my seventh birthday. We came across the desert and I didn’t really understand why. I just remember saying goodbye to my grandparents the night before, and not realizing, at that moment, that this was going to be the last time I was ever going to see them alive. I wasn’t even able to go to their funeral – I just never saw them again.

I remember arriving in Phoenix, Arizona, to a predominantly Latino community. We were sharing a home with my dad’s friend and there was a lot of friction with the other family. My parents worked all the time so that our family could move into our own place – my dad, in a restaurant kitchen, flipping burgers; my mom, at a laundromat.

Eventually, my parents were able to rent a really old house that we could move into. It had an unfinished bathroom and a huge, empty pool that we had to use for showers while waiting for the bathroom to get finished. We would just stand in the pool and hose off using the garden hose.

My parents started making traditional Mexican candy out of our shed, and it became a way for our family to earn money. All of us kids would help my dad, whose dream was always to have a candy factory in America. We would make the candy and deliver it to Mexican stores and supermarkets. We all had to work all the time. We didn’t go to Disneyland during the summers – we didn’t do things like that. We were always working in the backyard, or taking care of our younger siblings. But, as challenging as it was, now I’m grateful to have had those experiences. They were, in so many ways, teaching me entrepreneurship, and helping me develop a strong work ethic at a young age.

JS: What happened to the candy business?

SRH: My parents didn’t have the tools or basic knowledge needed to really scale a business in America. When the business started to grow, stores started requiring things like nutritional labels – things that required money and that my parents, being undocumented, didn’t have access to. If you are an undocumented immigrant, you don’t have access to capital.

Over time, there were a lot of hurdles that became more and more challenging. Eventually, my dad entered into a predatory deal with a shady investor, and we ended up losing everything. Both my parents went back to work. My dad went back to a restaurant kitchen, and has been there ever since.

JS: What was school like for you in America?

SRH: It was culture shock. I remember at one point my teacher was speaking to me and I had so much anxiety because I just couldn’t understand what she was saying. That was one of the experiences that made me feel really bad about being in another country – because she didn’t try to help me. She was almost yelling at me while knowing full well that I couldn’t speak English.

Being a young Latina in the USA, that struggle to adjust in school was paired with the cultural nuances of growing up with a traditional Mexican family. I had frustrated immigrant parents whose only goals were to work and to succeed. My parents taught me respect and to have a good work ethic, but a young woman in that environment is also expected to keep her mouth shut. I didn’t feel like I had a voice and that made me very introverted. I didn’t feel like I fit in and I learned to cope by writing stories. I was always by myself and I would keep diaries and sketchpads under my bed.

JS: At some point you had to start sharing your creativity outwardly, though, or else you wouldn’t be where you are today…

SRH: I think it started in high school. By my freshman year, I already had a job – at a pizza place. I was helping my family pay bills, but I also felt like I had a little money now, so I could buy my own things. I would use it to do crazy things with my hair, or wear crazy makeup. That was a form of creative expression for me.

Then Myspace came about. People forget that Myspace taught my generation to be coders because we were using HTML to make our pages have glitter on them or whatever. I started getting passionate about working on my page. Then YouTube came along, and Tumblr, so now I was making videos and writing poetry. I had two different lives. I had my life with my friends at school, where I felt understood and could express my creativity. Then I would go home and work.

JS: Did being undocumented affect your relationship with your friends at all?

SRH: During high school was when I started realizing the impact of being undocumented – when junior year came around and everybody was getting ready to take the SATs and apply for college. College fairs would come to school and counselors would ask you what your plans were, but these were things we didn’t even discuss in my home. We didn’t talk about college or furthering our career – because we were undocumented. We couldn’t tell people about our status because something bad could happen, so it was this secret that I was just holding. I didn’t tell any of my friends. I didn’t have anyone to talk to about it.

JS: I can’t imagine what kind of burden it must have been, as a young person, to feel so cut off from all the opportunities that your friends had, and have nobody to talk to about it.

SRH: It was a really depressing time because all of my friends were getting ready to go to college and I thought, “I’m going to be stuck here in Arizona, working at a low-end job forever, because I don’t have a social security number to get a real job, or to go to college.” Even if I had good grades, I couldn’t have gotten a scholarship. I couldn’t apply for financial aid. There was no DACA then. Being a Dreamer wasn’t a thing yet. It was really, really challenging. I didn’t know what to do.

When I was 19, I actually got married. We had a child together, but it just didn’t work out. Three years into the marriage, I had to be really brave and say, “This isn’t working.” It took a lot of courage because my parents are so traditional, and religious on top of that, and they were just so upset. Nobody in their life had ever gotten a divorce or even mentioned it, and it was almost like they disowned me. That was when I knew that whatever was going to happen with my life, I would have to make it happen. I packed up my bag and I just left home, and came to Atlanta.

JS: Why Atlanta?

SRH: The guy I was married to was from Georgia. While married, we had visited his family there, and we had gone to Atlanta. There was a lot of hype about Atlanta, and I was impressed. It was a bigger city. [Laughs] It was where Ludacris was from! It was a place I had only seen from a distance, but I knew I could find opportunity there.

Now when I look back, I think, “That was really stupid. Getting a one-way ticket and coming to a new city with my little boy and just $50 in my pocket?” I don’t think I would do that now.

JS: It sounds like something out of a movie. Did you have a place to stay when you got to town?

SRH: Yeah, I had found a room to rent through a Twitter connection. When I got to Atlanta, I went on Twitter again, and also Tumblr. I had built an online community of creatives by that point and one of my friends said she could find me work at her restaurant. I went there and they hired me on the spot. Then I found a second job. I found a pre-K that would take my son and I would drop him off, come to work on the bus, then go pick him up from school – on the bus – and then come back to work the dinner shift at the restaurant.

At the same time, I was meeting so many cool people in Atlanta. It’s full of young people with dreams, and everybody’s hustling and working and trying to make things happen. That was really inspiring. I started thinking, “You know, there are a lot of people here who are really creative but that haven’t had the same opportunities as other people. I should do a YouTube series about them!”

And that’s what I did. I just started doing YouTube videos with a friend. I called my show The Sam Offtharecord Experience. I was just out there, telling stories, going to concerts of musicians I liked. I would say I was press and they would let me in, then I would write stories and sell them to publications. I would just cold call or send emails to publications I liked and sell them my reviews for $40 here or $50 there. I was just doing a whole bunch of creative things and it felt good. It was a high that kept me going. I was creating something. I was doing something that I was passionate about and meeting cool people along the way.

JS: At some point, you turned your creativity into a full-time career. How did you go from working at restaurants and writing concert reviews to running a creative content agency and digital magazine?

SRH: There was an entertainment lawyer who used to eat at the restaurant I worked at, and he was a really nice guy who would always tip well. One day, I gave myself a pep talk, and I walked up to him when he was eating and I said, “Hey sir, I’m sorry to bother you, but I know you work with a lot of cool people and I want to know if you would have some time to check out my YouTube channel or give me some advice.”

He said, “Yeah, of course!” and he gave me his email. I sent him the YouTube link and he emailed back saying, “I love how you tell stories, but I really don’t know what to tell you right now. I know that one day someone will come to you and they’ll offer you a big contract, and I will be there when they do to review that contract for you.”

[Laughs] I thought, “Okay… That wasn’t what I was expecting to hear, but thanks?”

Then I think a year passed. Maybe longer. I continued to make Instagram content and my YouTube channel was picking up steam. I wasn’t super famous, but the Atlanta creative community knew me. I could walk down the street and a young person would be like, “Hey, Sam Offtharecord!” I started a hashtag called #livecreateinspire for the grassroots creatives out there, the edgy creatives – the ones that have no money but make s**t happen. The underdogs. They knew me. I could show up at a concert and they would let me in at the door because they knew who I was. I was becoming a hometown name.

Then, a company in Chicago caught a whiff of what I was doing. They called and said that Miller Lite wanted me to go to the Latin Grammys and make some Behind the Scenes videos and things like that. I got really excited about it because I thought that was my way out. I thought that I was going to start making money doing what I loved.

So, I talked to that lawyer again. I said, “You won’t believe this – remember when you told me somebody’s going to give me a contract and you would review it? Well, I have one!”

He didn’t remember that he had told me that, but he said, “Okay, I got you…” [Laughs] Well, it ended up costing me $1,000 for him to review the contract!

JS: What a guy!

SRH: [Laughs] He let me pay it off in installments, so it was okay. Except when I showed him the contract, he said it was terrible and that they were trying to own all my intellectual property. He said, “You’re not going to make any money from this. This is not good. Don’t be in such a rush. Take your time. You’re going to get somewhere. Just keep doing what you’re doing and trust your process.”

JS: That must have been such a letdown.

SRH: I was really heartbroken. I was so broke then. I was exhausted from working so many jobs, and staying up late making YouTube videos, and being a mom, and having no family in Atlanta. You can’t afford vacations when you’re poor. You can’t go to the spa. I walked everywhere. I didn’t have a car. I was just exhausted.

I started thinking that maybe it was just time to leave Georgia. I was ready to do it, but something in me said, “Go up to the lawyer’s office one more time. Make this the last thing you do before you leave.” I was just a waitress and I was still intimidated by people like him, but I worked up my courage and I sent him an email.

JS: What did you say to him?

SRH: I said, “I know I can’t afford your hourly rate, but can I have just five minutes of your time? I just have one last question.” He responded, “Sure, come on up.”

His office was at the top of the building that my restaurant was in – you could see all of Atlanta from up there. I went in and I just started crying because I didn’t know what else to do. I said, “It’s taken a lot for me to do this. I don’t like asking people for help, but I really need somebody to give me some direction. I’m not asking for a handout. I’m just looking for an opportunity. I’ve never told anyone this – but I’m undocumented and I can’t even afford to file for DACA because I’m a single parent. But, I’m doing my best. I’m working hard. I’m taking care of my son. I’m giving life my all and I just don’t know what to do. Nothing has happened for me. Do you know anybody that can teach me something? Give me some guidance?”

JS: [Laughs] This is so dramatic. You have me on the edge of my seat. How did he respond?

SRH: [Laughs] I think he felt a little sorry for me, which I didn’t like – I don’t like people feeling sorry for me. But, at the same time, he was impressed. He was like, “Wow, this person is really willing to work for this.” He said, “I personally don’t know what to tell you because I’m an attorney, but I have a friend who runs a multicultural ad agency called Matlock. It’s been around for 30 years and he may be able to give you some guidance.”

That was just the little bit of hope that I needed at that moment – and he actually followed through! He scheduled a meeting and said, “We’ll walk over there tomorrow. Dress nice and I’ll take you over there myself, and you can ask him questions.”

I didn’t really have any nice clothes then. I had green hair and piercings and tattoos, and a trench coat that I had found at a thrift shop, [laughs] which I thought was nice at the time. That’s what I was wearing when I met Kent Matlock, the agency’s chairman and CEO. We went into his office and he said, “Okay, young lady, show me your portfolio.” I said, “I wish I had a portfolio – but I’ve never even had the chance to go to college. I moved here by myself to Georgia four years ago. I’ve been working hard ever since and what I do have is a YouTube channel and an Instagram account.”

He said, “Okay, show me what you’re talking about.” I started showing him my Instagram videos and he said, “This is really cool! Your storytelling is so great.” He was impressed by the work and by the fact that I had learned how to use Photoshop and Adobe Premiere on my own.

He said, “You know what? I’m going to make you my personal assistant.”

JS: Wow, just like that, he made you his assistant? This really is out of a movie.

SRH: [Laughs] I know! Unfortunately, though, I was a terrible personal assistant. It was a bumpy ride in the beginning and I bumped heads with Mr. Matlock a lot. At a certain point I said, “I’m leaving,” and so he said, “How can I help you get to where you want to take your creativity?”

I told him, “Well, I want to make videos.”

So, he started giving me small creative projects, like doing a video for Macy’s that entailed going to their office and filming a private meeting with the CEO. Or doing a YouTube video with the granddaughter of Martin Luther King. Little projects like those allowed me to prove myself and eventually, Mr. Matlock said, “You know what? You need a business partner.”

JS: What does that mean? How did being a business partner with his agency manifest?

SRH: He wanted to be a partner with my digital production entity, Offtharecord (OTR). Matlock does a lot of great public relations work, but when it comes to digital video – Instagram stories, etc. – OTR can help them troubleshoot and help them introduce new services for their clients. In return, Matlock has been around for more than 30 years. They are an authority in the space and they can help us get new clients. We’re young and crazy-looking, and having that name behind us can be hugely helpful.

So, now my little digital agency has a staff of its own and we’re growing and starting a buzz around Atlanta. Our first big client that we got on our own, outside of the work Matlock was giving us, was the Ms. Foundation, which was cofounded by Gloria Steinem. We do the storytelling for their grantees. We’ve been doing it for three years, and our budget increases every year. We have worked with Stacey Abrams. We have done projects with Johns Hopkins Hospital on transgender youth, so that they could serve them better. We get authentic stories because we talk to people in a real way and we cut out all the bulls**t.

JS: I can’t imagine how gratifying it must feel to take your creativity to this incredibly high professional level after all you’ve been through.

SRH: It really is. I was in a very vulnerable place when I came to Atlanta. I was unable to reveal that I was undocumented and there were so many jobs that would underpay me because I didn’t understand what value I was bringing. Mr. Matlock had the opportunity to take advantage of me and of my work, but he is a principled person. He believes in principled entrepreneurship. It is important for him to elevate entrepreneurs.

I feel really grateful that my journey brought me to him, because even though our first introduction was funny – in retrospect – we both have learned so much from each other now. That is a lesson that I will carry for the rest of my life: somebody didn’t discover me or make me – they opened the door for me and allowed me to grow. In return, I now have a pathway to be able to do that for other people.

JS: How have you been able to pay it forward?

SRH: As OTR has grown, I’ve been able to hire creatives that I used to see working hard and being passionate about their craft, but who couldn’t always afford an educational background and never had access to an agency like ours. I’ve also been able to license music directly from musicians I know, who aren’t famous, but who are really great. We’ve been able to create a network that provides work for creatives and pays musicians in our community.And now, I am even relaunching my dad’s candy business and we’re starting to move into the market here in Georgia. We launched our website recently and have already been getting plenty of orders. I named the company El Sueño Rico, which means “the sweet dream.” It’s a name that has the sweetness of candy, but also pays homage to my dad’s American dream. My grandpa was also a candy maker so I have the story up on our website and that story is part of our brand.

JS: Creativity has brought everything full circle. Your self-taught storytelling and marketing skills have helped your career, your community, and now, your family. That’s pretty cool.

SRH: It’s really cool! Now that I’ve been an entrepreneur and have more tools and resources than my parents did, I feel like I can lead the charge. I wish more Latino immigrants had what I have because our community would grow so much more.

JS: Despite all your amazing success, the sad truth is, we are not living in a great time for undocumented immigrants in America. Has your experience made you feel optimistic about where your community is headed?

SRH: I will always feel hope for the future, because I feel like when we lose hope, we lose our ability to continue pushing forward. What is going on is saddening and maddening, but the flip side is that these things have been happening already, and those of us who have been living it, and have been seeing our communities attacked, and who have known firsthand the stories of children being separated from their families – we know that this is not new. This has been happening for a long time. It’s just that the world can see it now. Now, there is visibility, and that is necessary so that we can fix it. Now that we know that it exists, more people will be able to be a part of that change.

And, my community can speak up now and be a part of the transformation. We didn’t have that privilege before. You couldn’t openly be a Dreamer and be proud of it. We didn’t have a Super Bowl committee putting Dreamers up on a mural!

In a country where undocumented immigrants face an uphill battle just to subsist, Ramirez-Herrera’s self-made rise from voiceless youngster with nowhere to turn to sought-after entrepreneur, seems nothing short of miraculous. But to hear her tell it, there was nothing magical about it. At the end of our interview, I asked if she might have some words of wisdom for other young dreamers who yearn to rise up and take their creativity to the professional level. She said that for them, as for anyone, there is only one pathway to success.

“You have to get over your fear and just do it,” she told me. “If you want to be a storyteller, just tell your story. You don’t need to have the perfect camera, or an education, or a lot of money. All you have to have is passion and action. Start with what you have and build from there. You will learn and grow along the way. Empty pockets can’t hold people back. Empty minds and empty hearts can.”

With that, Ramirez-Herrera went back to her office in the heart of downtown Atlanta, and she got back to work.

Photos courtesy of Samantha Ramirez-Herrera