By Justin Sanders

If filmmaking is the creative industry’s most collaborative medium, then it follows that the job of production designer is creativity’s most collaborative position. Tasked with envisioning a project’s entire look and feel onscreen, the production designer touches nearly every aspect of life on set.

“The conversations that you have go across the board,” said production designer Cecil Gentry, whose long list of credits include the indie hit Swimming with Sharks, the HBO original The Leisure Class, and the Hulu horror anthology series Into the Dark. “It’s myself and the costume designer. It’s myself and the director. It’s myself and the director of photography, etc. etc. Then you’ve got the studio who will weigh in. You’ve got the network who will weigh in. It’s totally collaborative. And that’s all before you have to hire the folks to handle the nuts and the bolts of all of it.”

That’s right, the intensive, mentally taxing act of design is only the beginning of Gentry’s role – he must also pull together the people, materials, and other resources necessary to make that design a reality – not to mention create and closely manage the budget that pays for all of it. That’s why, though Gentry bypassed film school to learn his career on the ground, his formal business education comes in handy nearly every day of his life.

Could production designer be the most challenging job in show business? It certainly requires one of the most diverse skill sets of any role in Hollywood. Fascinated to find out what makes such a person tick, CreativeFuture visited Gentry’s Los Angeles apartment to talk about working with Alfred Hitchcock’s former production designer, staying calm amidst the chaos of the HBO reality show Project Greenlight, and building a Christmas tree lot in the dead of summer.

JUSTIN SANDERS: Let’s start with the basics – what does a production designer do exactly?

CECIL GENTRY: The job of the production designer is to create the look for the show. It’s part architecture, part interior design, part researcher – essentially, the job is to bring to life whatever’s on the page, to support the narrative and tell the story visually.

JS: It sounds like it requires a very specific skillset. How did you get started down this career path?

CG: I was working in the advertising industry, doing work as a media buyer, but I was really not happy because it was not creative. I didn’t want to end up in some dead-end job, hating it, so I moved to Los Angeles and started snooping around in the film industry. I discovered the title of “art director,” the job that traditionally leads to becoming a production designer, basically by going through a film dictionary and coming across the job description. I was like, “Bingo! That’s me.” I read it and knew deep in my soul that it was who I am.

JS: So, once you had plucked your career choice out of the dictionary, how did you then go about pursuing it?

CG: I made some contacts, and I started working for free as a set decorator, which is where you build the skills needed for art directing, and, ultimately, production design. I set-decorated for quite a bit of time for commercials and music videos, building relationships and studying architecture in my own time.

JS: Looking at your IMDB page, you actually have very few art director credits. It’s almost like you jumped straight from set decorating into full-on production design. How did you know you were ready for such a leap?

CG: It’s not like a corporate job where you get promoted. You’re an independent contractor, so you’ve got to believe in yourself a whole lot. You’ve got to know when you’re ready. So, I went out, I got business cards, and I was like, “I’m ready to make the transition. I’m ready to production design now.”

JS: Your confidence was not unwarranted. Your very first production designer credit was not just any movie, it was the 1997 indie hit Swimming with Sharks – a personal favorite of mine. How did you land such a choice gig right out of the gate?

CG: I had been set decorating for a really prominent art director on commercials and music videos, and I had been talking to him about getting into film – for me, commercials didn’t have the satisfaction of a juicy narrative. The Swimming with Sharks job was offered to him, but he wasn’t interested in narrative. He said to me, “Listen, I just received this script and the cast is good and the story is really good. You’ve been talking about film, so take a look at it – and if you’re interested I can make the introduction.”

So, I read it and was thought, “Oh my god, this is great. I could totally sink my teeth into this. It’s fantastic!” The art director made the introduction, I went in, had the meeting, and got the job.

JS: Did working on Swimming with Sharks propel your career forward?

CG: It did. That little engine proved to be quite a job-o-naut. I got an agent from that, and I believe it’s now required viewing in many film schools. It’s on the syllabus! I’ve met film graduates who have told me they had to watch it. It’s pretty iconic.

JS: But you yourself did not attend film school, correct? You’re self-taught?

CG: Yes! I went to school for business – though I do use that degree every day. As a production designer, I’m in charge of budgets. I have a fiduciary responsibility to producers, the studio, and the network. So, those business studies have definitely proven to be invaluable.

JS: Did you ever consider going to film school?

CF: Yes. At one point I was going to get an MFA at American Film Institute. I got accepted there and I met Robert Boyle, who headed up the production design department. Because I had already been working, he and I decided that instead of going to school and taking myself out of the market for two years, why don’t I just let him mentor me? That became a great relationship. Robert was Alfred Hitchcock’s production designer. He’s no longer with us – he died a few years ago, but he was a huge influence on me.

JS: What did you learn from him?

I learned space – negative space and placement, especially with regard to building sets. It was a technical education and there were a lot of tricks of the trade that I picked up along the way. Production design is a psychological game, you know.

JS: Do tell!

CG: Well, certain colors will make you feel a certain way. Certain shapes and certain objects will create an emotion, and it just backs up the dialogue. In advertising, we call it “psychographics,” and you just figure out psychologically where your demo is. How does the person you’re trying to reach think? You want to put things in front of your viewer that they can relate to and that keep them coming back. It has to do with socioeconomics and a lot of different things. If you’re targeting the right audience both visually and verbally, then you’ve got them. It keeps your viewer coming back.

JS: How do you start each new project?

CG: I get the script and I read the script. The first time is just for content. I’m seeing props, I’m seeing furniture – I’m seeing the whole kit and caboodle. Then I go back and read it again to break it down, to figure out how many locations we have and just, basically, what is the story? What are we trying to communicate to the audience and how do we do that visually?

After doing that breakdown, I let it sit and marinate, and then I will start designing.

JS: And what does that design process entail?

CG: We’re in a technological age, so I hit the internet right away and I start pulling visual references. I may do a sketch or two, but there are tons of resources out there so mostly I’m just pulling. I’m usually able to tell the story visually from start to finish using nothing but images that I’ve pulled. Sometimes, you can get so specific with just online references that you can find an exact image match with what is in the script. Which is great – that’s when you know you’re on the right track.

Then I’ll compile all my visual references into a look book and present it. It’s a huge conversation between the director, myself, and the director of photography, and then we bring in the costume designer. The four of us sit down and really hammer out what this thing needs to look like.

JS: What happens after you’ve settled on a vision?

CG: Hiring a crew. I’m looking for a set decorator. I’m looking for an art director. If there’s any construction that needs to happen, I’m looking for a set designer, a construction foreman, and a construction crew. Then there are all the props…

A lot of times what I’ll do is hire leads – known as the “keys” – such as the set decorator, and then they will hire the support crew. The set decorator, for example, will hire the shoppers, the buyers, the swing gang who are responsible for picking up furniture and dressing sets. The set decoration department may have the lead decorator and then a crew of up to 10, or even a couple of different crews that we switch out because of the nature of the shooting schedule. Sometimes we need two crews to get it done.

JS: You were part of a production that put that behind-the-scenes process under the spotlight – HBO’s The Leisure Class. Tell us about that film and why working on it was so unique.

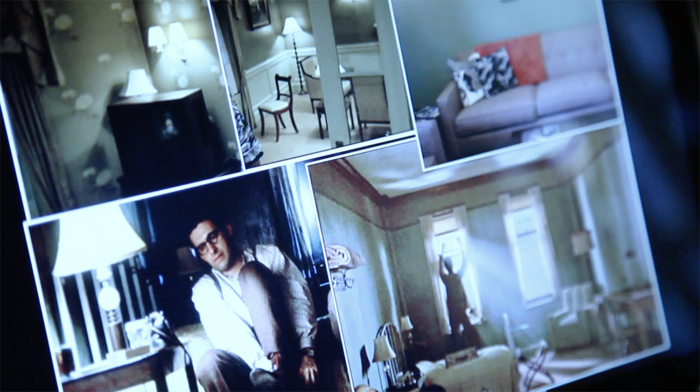

CG: That movie was the focus of Season 4 of HBO’s Project Greenlight television series, which hands an untested filmmaker the chance to direct a feature film, then documents the process. It was interesting for a couple of reasons. We had the making of the movie itself, which we were prepping and shooting as normal, and then there was the behind-the-scenes portion of it where we were all mic’d up and having conversations. It was part reality show, part feature film production.

JS: Was that nerve-wracking at all?

CG: Yeah! You’ve got every word being recorded and sometimes the conversations would get heated because you’re trying to make decisions and the director might not necessarily be on the same page as the producer – as you saw if you watched the show. There would be times when we would all be in a room, having a creative meeting, and all of a sudden, the cameras would show up and right away you knew that something must have been said in the other room and now they were coming our way because they wanted the dirt.

JS: The way the show was edited, it made it look like Leisure Class director Jason Mann was in way over his head at every second, butting heads with everyone around him.

CG: [Laughs] Because that’s what makes the show, right? Jason was great. He was a stickler for what he wanted. He was committed. The original idea was to shoot it digitally, but he fought for film and he got it. The winning screenwriter from the first season of Project Greenlight, Pete Jones, was brought on as a writer and support system for Jason. I remember Pete saying one day, “Jason, if you start giving in, you will end up with a film you didn’t want to make.” So, Jason wasn’t having any of it.

JS: The film he ended up making, with your help of course, was kind of a comedy of manners set in modern times. Are there certain genres you prefer working in over others?

CG: I’m a bit of a minimalist when it comes to design. I mean, I can do it all, but I prefer a science-fiction meets psychological thriller type vibe. That’s the kind of stuff that really excites me as opposed to, say, romantic comedy, where I find that there’s not much of a design challenge. I tend to stay away from the rom-coms and go toward these sci-fi worlds that you get to create from nothing. This is why Hulu’s Into the Dark is perfect for me – because it’s right up that alley.

JS: I’ll say. Into the Dark, a horror anthology series from Blumhouse where each episode centers on a different holiday, seems like a production designer’s creative dream come true.

CG: Yeah! We’ve had a Father’s Day episode, a Valentine’s Day episode. There’s a Christmas episode… Each episode has a different director and a different cinematographer, so it’s a totally different experience, with different relationships, every time out. You’ve got to be able to quickly jump into gear and work with different people and different personalities.

JS: What are the challenges of designing for a show where nothing, not even the people involved, is the same from episode to episode?

CG: It’s oftentimes stuff you don’t think about. The Christmas episode for instance, “Pooka,” had to actually be shot in the summer. So, it was quite a challenge to find Christmas décor. We needed a Christmas tree lot, and we at first had talked about shooting at a Christmas tree farm up north. We ventured up there and when we got there, it just didn’t look like how it was presented online. There were hardly any trees and they were small, so we ended up ordering a bunch of trees and putting everything under a tent – because it was 95 degrees out. A lot of the story occurs at that lot, so if we didn’t have the tent it would have just been unbearable for talent.

JS: I have a memory involving your line of work from my days when I was an actor. On one of my first film sets, the production designer showed up with this really cool prop involving a beer cooler that emitted magical vapor when it was opened. I remember thinking how cool it was that this guy could just go and make something like that.

CG: Yeah! That’s what we call a hero prop, where it’s got to perform some sort of special functionality onscreen. At the level I’m at now, a prop like that is a huge collaboration. You’ll have sound incorporated with that prop, and special effects for the steam or smoke. It’s got to be rigged, it’s got to work on cue with the action of the scene. It’s going to involve a lot of moments and components for me to coordinate.

JS: Moments and components! I like that. What’s an example of a hero prop you’ve worked on recently?

CG: The very first episode of Into the Dark, “The Body,” has a Halloween theme. It follows a hitman who kills a big Hollywood celebrity and then wraps his body up and makes it look like part of his costume. Then he loses it and has to find it again.

Obviously, the body prop had to be great. The guy had been murdered, but it was also all meant to appear as though it was just part of a Halloween costume – [laughs] even though it really wasn’t.

So yeah, that was a huge, complex hero prop, and while I was involved with the design of it, the design was only the beginning. Once the studio signed off on the design, it was up to us to get it built. We needed to first find the body. There are a lot of dummies out there that don’t look quite real. We ended up going with a company who provided a realness with its mannequins – [laughs] hair on the ankles and the feet and so forth. My prop master had to wrap it in cellophane and give it a wax paper type look to give it opacity, because we needed to see blood. There also needed to be some movement with the prop because there is a moment in the script where the corpse’s muscle twitches. So, animatronics were a part of it as well!

JS: So many details that people unfamiliar with this profession wouldn’t even think about.

CG: You don’t know the half of it. I recently had a situation where a car had to drive into a dumpster – my department provides the dumpster, but special effects and stunts got involved as well because it had to be made safe. We had to anchor the dumpster to the ground. So, there’s all this crossover for what seems like a plain old dumpster, and I’m involved with pretty much every conversation. It’s not that I’m doing all of those jobs. I’m not in the special-effects union. I’m not a stunt coordinator, I’m not in the costume guild, and I don’t do hair and makeup – but because I’m the production designer I have a say-so in each one of those areas.

JS: What advice would you have for someone who wants to become a production designer?

CG: Meet people. Make connections. Make contacts. Definitely view a body of work. Just immerse yourself in films and television shows, and go for it. It’s creative, but it’s also a business. You’ve got to put yourself in the right situations. You’ve got to understand and know what it is you like and prefer creatively, and focus on that. You’ve got to be able to sell yourself. You’ve got to be really proactive – because it’s not the kind of situation where people will come knocking on your door. You’ve got to prove yourself. You’ve got to get out there.

JS: Production design seems to, more than most jobs I can think of, involve so many spinning plates at once. How do you stay calm and collected in the thick of it all?

CG: You have to kind of have that nature already inside you to be a production designer. It has to be built in – because if it isn’t, craziness can ensue, and nobody wants that.