By Justin Sanders

Happy New Year! We all went through a lot in 2020, so let’s take a breath and turn the page on one of the toughest years any of us can remember.

Make no mistake – our creative industry has a tough road ahead. We have to somehow bounce back from a pandemic while continuing to battle systemic online piracy. We have to continue holding corrupt internet platforms accountable and we have to keep the momentum going in Congress, fighting for laws that strengthen copyright and ensure we get paid fairly for the work we do. And somewhere in there, we have to keep making amazing creative works that enthrall the world.

But before we get to it, the new year is a time to breathe, to reflect, to recharge. You can start right here, with a dose of motivation by way of our inspiring conversation with sculptor Guy Pederson.

The longtime resident artist at Indian Springs Resort in the small Napa Valley haven of Calistoga, California, Pederson lives and works “across the street from the grocery store, one building removed from the hardware store,” he told CreativeFuture. “And that’s my world.”

Pederson does not need anything more than that. Years ago, he made a pledge “that I would just follow creativity wherever it would take me,” he said. Since then, he has lived an artistic life of rare dedication, working up to 15 hours a day, turning thousands and thousands of tiny component scrap parts into other-worldly figurative sculptures that seem to ripple with a dreamy life of their own.

When Pederson breaks from creating, it is usually to help others create – by way of his work with orphaned children at the Operation iDream community school and clinic in Zambia, or simply by listening and offering guidance to the many young artists who visit his gallery every year.

“With every breath – from our first breath of life to the final breath we exhale – each of us Is a creative soul, an artist, with a mind of unlimited creative ability,” Pederson said. “With each word you speak, your breath is strengthened by the breath of countless millions – that is the power of art.”

May we all continue to breath together as we embark on another trip around the sun.

JUSTIN SANDERS: Your art is unlike anything I have ever seen before, Guy, so let’s start there. How did you develop this unique style of sculpting?

GUY PEDERSON: I began to focus on sculpture about 10 years ago. For decades, I literally drew every day and that provided the foundation for my current work.

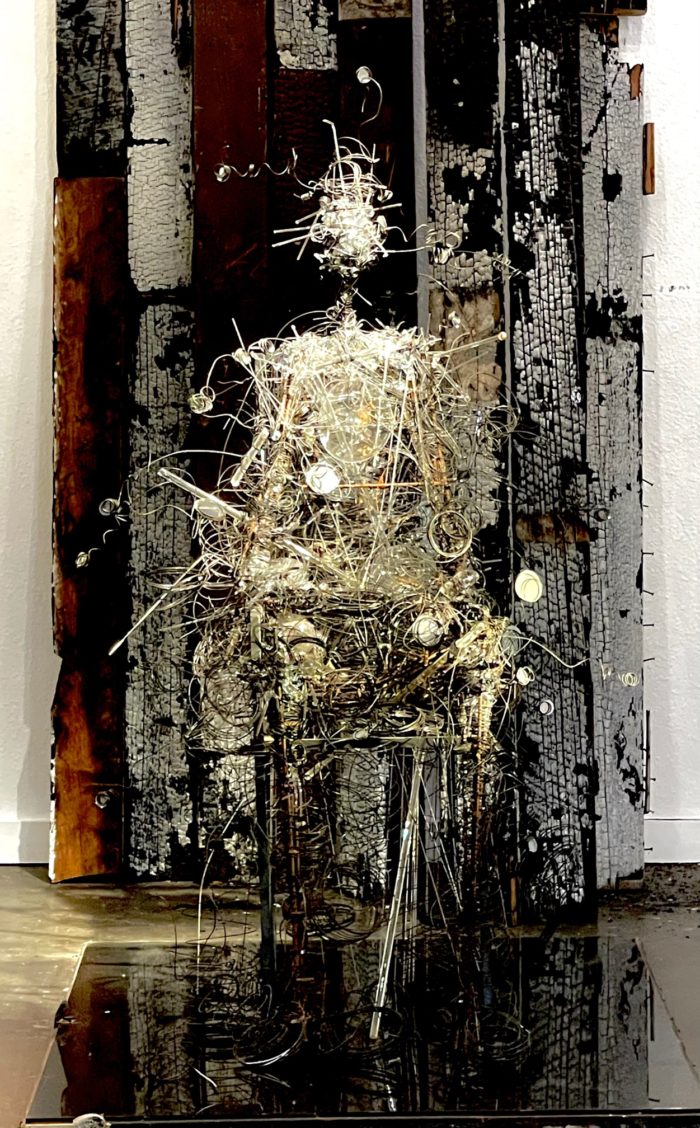

I create a lot of assemblage figurative works. When I start a sculpture, it begins very simply, gradually becoming complicated, and then some of them become extremely complicated. Often the sculptures are very personal to me, incorporating objects from boxes of things that I’ve saved over the years. Mementos from parents, grandparents, friends, and a lot of materials from my childhood. Now, I’m sending those memories and stories out into the world in the form of sculpture.

JS: How does your background in drawing inform the sculpting?

GP: The sculptures are based on drawings – just not specific ones. I want to let the work evolve in unexpected directions. Because many of the sculptures are assembled and welded together, it’s very easy to transition from one form to another, and I readily do that.

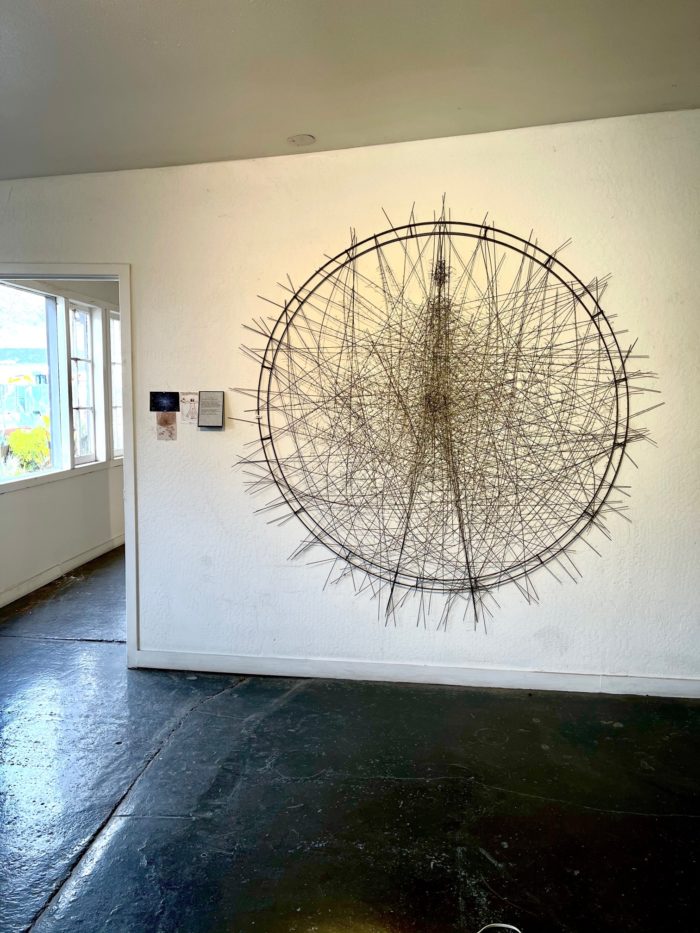

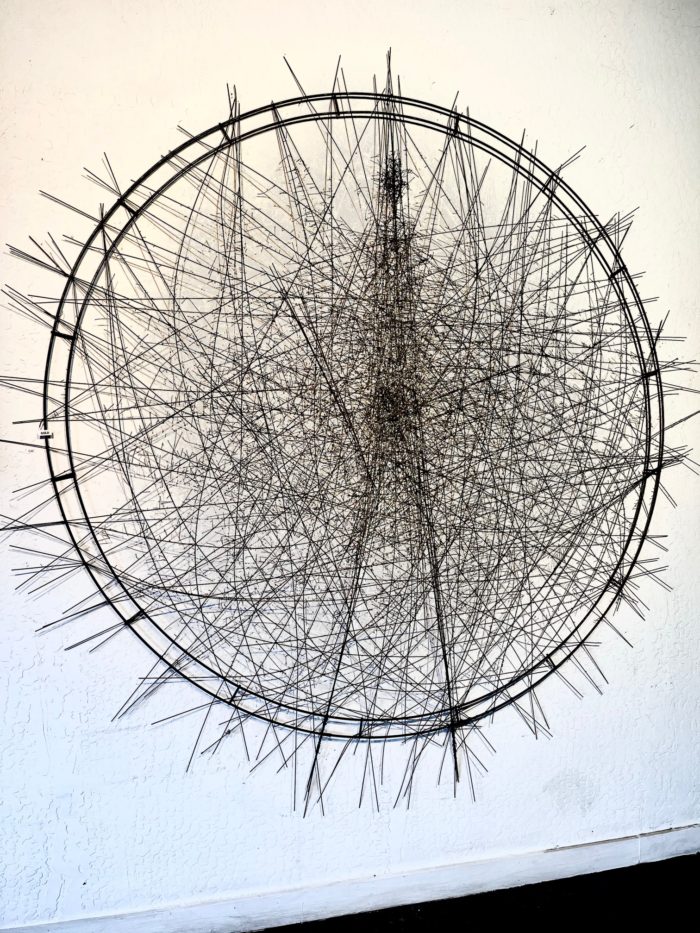

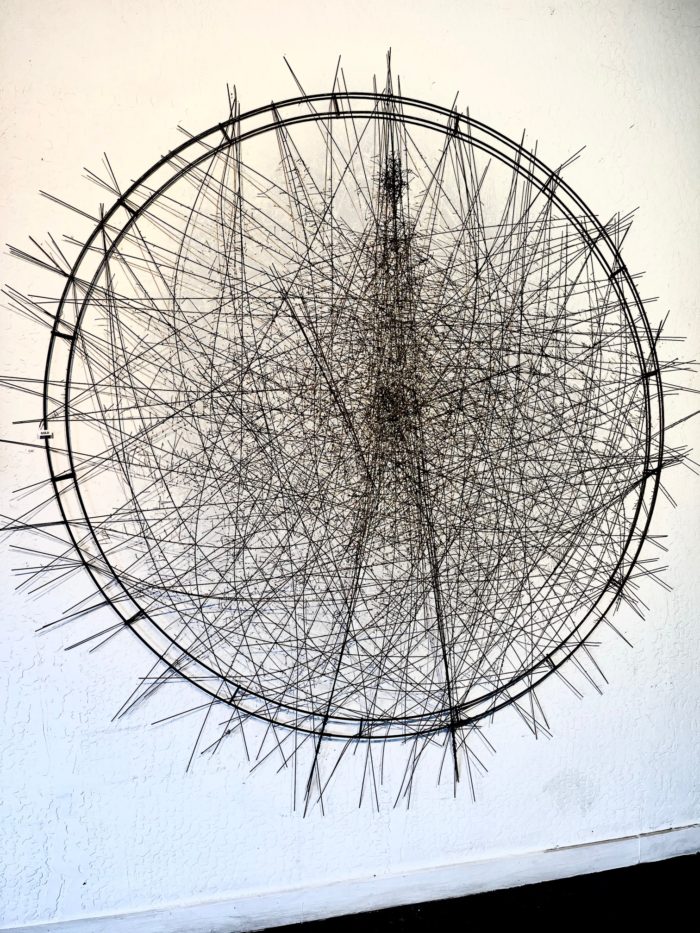

JS: You have a series of circular sculptures that recall Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man drawing. What does this drawing mean to you?

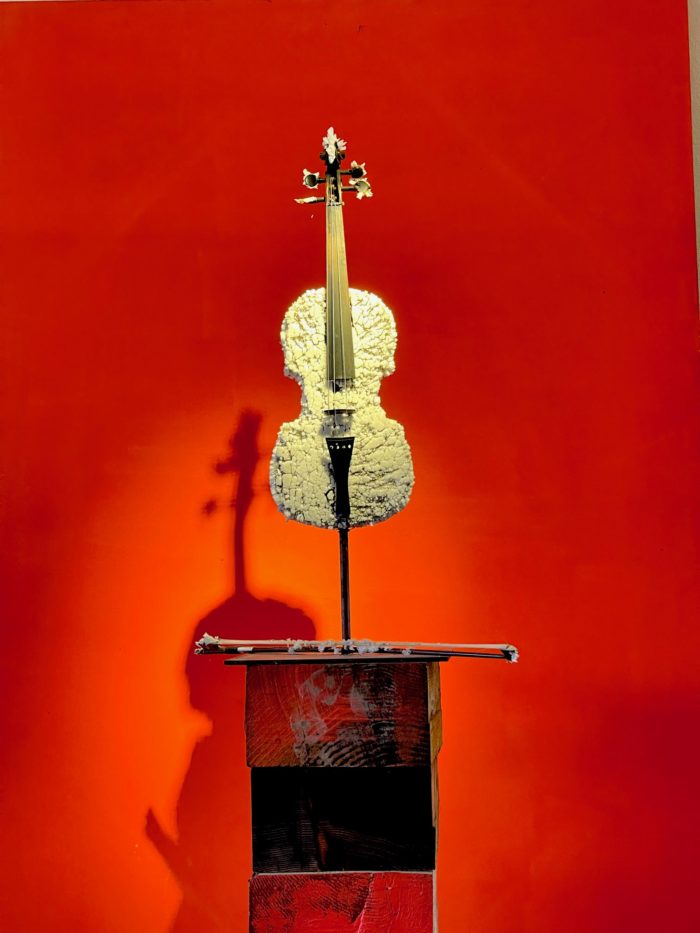

GP: The figures in those sculpture are fragile and complicated. I usually create a geometric structure to add support to the figure. I realized that putting a figure in the middle of a circle would automatically reference the famous Vitruvian Man drawing. At first hesitant, I eventually embraced the idea. The concept took me on a creative journey through history, ancient cultures, and the Renaissance – ultimately concluding with contemporary physics. A series of lost texts by Vitruvius were rediscovered during the Renaissance, which started a collective obsession with the principals of “the golden mean,” or “Golden Spiral,” inspiring artists, scientists, mathematicians, philosophers, musicians. The famous Stradivarius violin Is based on the Golden Spiral.

JS: And, at the quantum level, physical matter breaks down. What looks whole and beautiful from a distance is actually more and more destabilized and chaotic the closer you get to it. Your sculptures, with their thousands of tiny component parts, have a similar effect.

GP: It’s like what Einstein said about quantum: It’s “spooky action at a distance”.

JS: And then you have this whole other series of works that seems on the other side of the spectrum, where the sculpture just seems to grow organically out of them with a life of its own. Talk about your series of typewriter pieces.

GP: They’re intended to be dream objects, surrealist sculpture where the conscious mind says, “this doesn’t make sense to me” but the subconscious mind conjures up all sorts of explanations as to how this might have happened.

My studio is next to ancient geysers where superheated geothermal waters are mineralized by an ancient seabed. It is full of bones, skeletons, and shells from life on earth since the beginning of time. The hot water cools as it nears the surface, and calcium carbonate “flashes off” and forms beautiful crystals.

So, conceptually, the idea was to take a natural process with this extraordinarily profound history and create surrealist works of art from it. I couldn’t let it go.

JS: And why typewriters?

GP: For eight years I’ve experimented with many different objects and concepts. But typewriters are intriguing objects that have the potential for a lot of profound expressions. The first ones I did were dedicated to my father.

My father dreamed of becoming a writer. He put his dream aside and worked very hard taking care of his family. He gave to me the gift to dream. Those pieces are about gratitude.

The assemblage pieces are put together with welding, resins, tar, adhesives of every kind. Wrapping wires around wires. I have probably used every possible method you can think of to bind materials together in my sculpture.

I have a lot of welders come in here and say, “what the heck are you doing here?” I tell them I am a very bad welder and I make disasters. But they are interesting disasters and they offer an opportunity to try and create something unusual, unexpected.

JS: How did you come to be involved with Operation iDream, which brings education, training, and medical services to orphaned children in Zambia?

GP: Operation iDream’s founder, Samuel Sikapizye, became intrigued by my assemblage sculptures while visiting the gallery. They are created from thousands of little wires, pieces of glass, plastic, metals, and other parts. He told me, “My children sort the same types of materials and we send them to South Africa for recycling, which helps earn money for our school. Could you teach my children how to make art like you?

That was the perfect idea to present to me – I was immediately enthused. Some of the children are orphaned by diseases such as AIDs and malaria. Some have AIDs themselves. Others have lost their parents to conflict wars and have experienced violent trauma. It’s a lot to ask of children.

I hope and dream that they, too, have a creative future. As artists, we have the unprecedented opportunity to reach every person everywhere – with our creative efforts. We will all benefit if we encourage their creative future as well.

JS: How has this collaboration manifested so far? How have you gone about teaching art to children in Africa during a pandemic?

GP: Our collaboration is just beginning. The first project we did together, I sent paint and paper and had the children do paintings. They are just astonishing! They painted their dreams – what they’re thinking about, what they see and experience. I assembled the paintings together in a book and sent the first copy to the school so the children can see a book that they created. Most of them don’t have books at home.

I definitely hope that I will be able to travel to the school at some point. That was the first question Mr. Sikapizye asked: “Can you teach my children and when can you come?”

JS: Where are you from originally?

GP: I’m originally from Southern Oregon. I came to California about 20 years ago, to the Bay Area.

JS: Did you move to Calistoga to pursue your art career?

GP: I have been fortunate to spend my life as an artist, but I was at a crossroads. I came to California with the assistance of friends who were involved with a startup design technology company. I offered to volunteer at first and eventually became very involved with various parts of the company. The experience was a revelation to me.

JS: How so?

GP: It was a surprise, first of all, that I got involved with a tech startup at all, and even more surprising that I became useful at all sorts of levels. I realized that artists could be helpful at nearly every kind of company, in ways they probably don’t expect. Artists develop different ways of thinking and problem solving. The more approaches you consider, the more potential there is for creativity.

While I was working at the company, I ended up at a black-tie event at MOMA in San Francisco, where the keynote speaker was none other than Apple cofounder Steve Wozniak. His speech was extraordinary. I felt like he was talking directly at me. It was about creativity and why so many breakthroughs in tech have begun with creative people working out of their garage. It was no accident that they were the ones who were responsible for so many breakthrough technologies. It is about creative thinking. He explained that “experts” are frequently limited by accepting the perceived limitations. If you are unaware of the limitations, you may actually expand them.

As I left that evening, I was determined that I would not let limitations constrain me either, that I would just follow creativity wherever it would take me.

JS: Was making the decision to pursue art as a career scary? How did you make that leap?

GP: I think as artists, we constantly need to make a decision to continue to pursue creating art. At every moment of uncertainty, there was someone to offer help and encouragement. When I came to Calistoga, there were two people. One was Mitsuko Shrem and another, John Merchant.

Jan and Mitsuko Shrem co-founded a very famous winery called Clos Pegase, which included their extraordinary collection of the most influential artists of the 20th century.

Having Mitsuko’s encouragement had a profound effect on my courage to create experimental work, and It brought me to Calistoga. I was able to remain and create with the help of John Merchant. He provided great support including an incredible studio space that I’ve worked in for 10 years.

The opportunity was completely unexpected. When I came to this studio, I was under the impression I would have to leave after a year or two. So, I thought, “Okay, I’ll just get to work and I won’t think about building a business or exposure. Forget about websites and all the things that artists normally do to market themselves.”

Not knowing how long I would be in this space was one of the best things that ever happened to me – it drove me to work 15 hours a day, seven days a week. I realized I was given an exceptional opportunity. When you dedicate yourself in that way, inspiration is provided to you.

John gave me the finest compliment I have ever received: that “I worked harder than anyone he knew”.

JS: Are you worried about the future at all given these uncertain times?

GP: I think everyone in the art world is a bit uncertain as to how their future will unfold during these times. Here in Calistoga, and the surrounding area, we’ve also experienced devastating wildfires three or four years in a row. I have visitors come to the gallery who have lost everything. Many of them have the clothes on their back and a few other belongings and that’s it. And yet they walk in and still express gratitude for being uplifted by the art experience.

They have a great desire to read books, to see plays, watch films, listen to music, and experience all forms of art. It’s very meaningful, humbling, and gratifying that art can provide solace during difficult times. Art is the collective experience of all of us.

JS: What advice do you give young artists who come into your gallery?

GP: Many young artists come in and visit the gallery. Most of them are involved with the short-term goals: How do I get a studio? How do I pay for it? How do I find more time, space, energy, to create art?

I try to encourage them and tell them that this is a journey, and each journey is a little bit different. But whatever their path, they need to make the creativity the focus of it.

Most of them are way more tech savvy than I am, and that’s good. Social media and the internet can be an extremely valuable tool – but the one thing I’m always focused on is just creating art. And you need to make it as personal and meaningful as you can and try not to get discouraged.

I provide them art supplies when I can, follow their work, and I try to listen to them. And then I tell them that having a plan is good, but really – just make art.